Emerging Markets and their performance during global downturns

By Mark Copsey, Director of Allworths Wealth Management

Earlier this year in March, the coronavirus outbreak caused markets across the world to crash. A major sell-off in equities was seen across the board, causing prices to plummet.

Emerging markets were not immune to the drop, however, they bounced back quite rapidly. Initially, their value fell 24% from the year’s high, with the low occurring on 23 March 2020 but since then, they have increased by 18%.

But what is an emerging market?

In textbook talk, an emerging market is one that is in transition from a developing economy, that may be pre-industrial with low income, to a more sophisticated, industrial economy with a higher standard of living. Their tendency for higher economic growth suggests the potential for higher returns, however, their ‘developing’ nature means they may be more exposed to risk. Examples of emerging markets are Brazil, China and India.

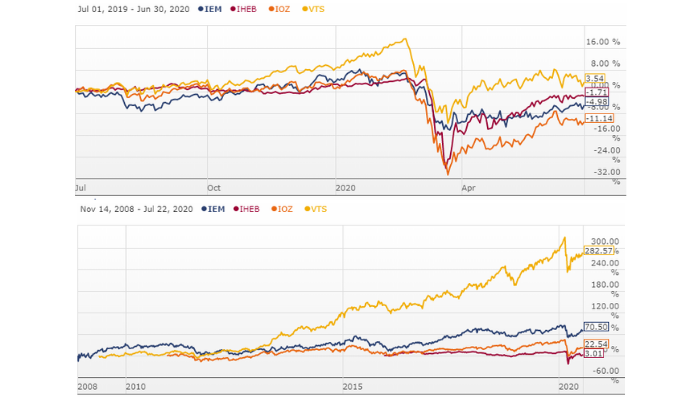

Emerging markets do get a bad rap, and this is probably unfair – as demonstrated by the two charts below. While the US market (as represented by VTS) has been the outstanding investment, in periods of volatility, the Emerging Markets ETF (IEM) and the Emerging Markets Bond ETF (IHEB) have performed a lot better than the Australian Market (IOZ).

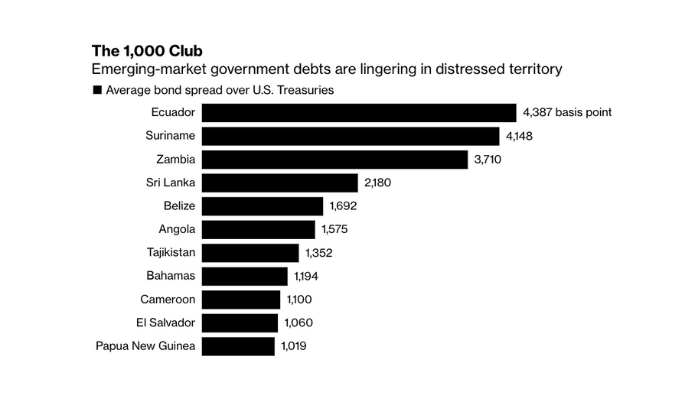

Whilst locked down in isolation, I did a lot of reading and listened to podcasts from some of the top thinkers in the world trying to make sense of emerging markets. It’s not easy to find clarity in a crowded market of opinions; what is easy is to get trapped in headlines like “Why There’s a Looming Debt Crisis in Emerging Markets,” reported by Bloomberg on 5 May 2020. Headlines like this make it sound like an open and shut case, but dig deeper into the details and there is more to the picture…

For example, while the Bloomberg article mentions 73 distressed countries, if you actually go and look at the list you’ll find only a couple are held in the IEM and IHEB ETFs and the countries listed are probably of no surprise.

Source: Bloomberg

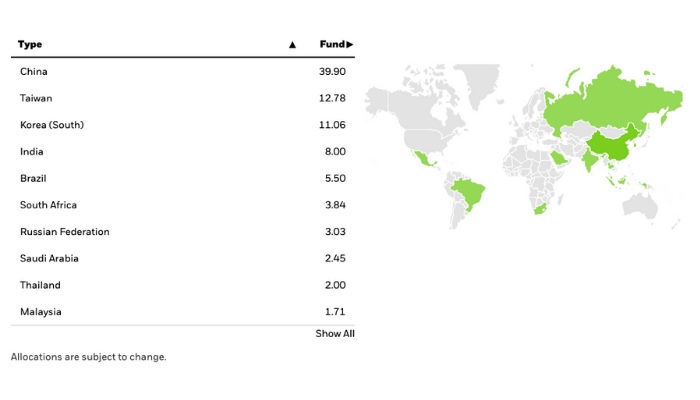

Top 10 IEM holdings by country

Source: BlackRock

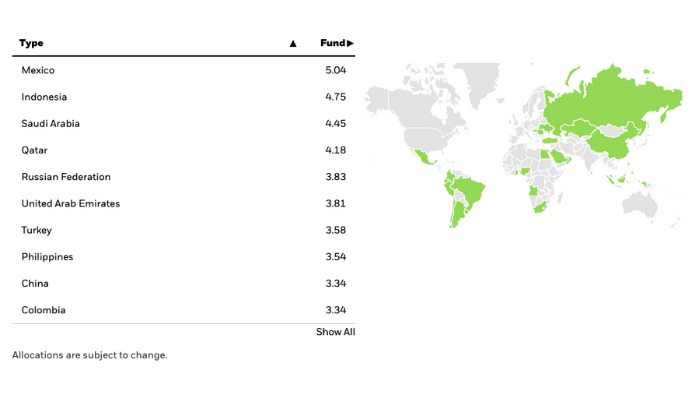

Top 10 IHEB holdings by country

Source: BlackRock

This goes to show how the whole category of ‘emerging markets’ gets a bad rap, even though individual countries and markets are not all the same from an investment point of view. Maybe these investments have been unfairly treated and are worth another look.

Additionally, a report by Van Eck reminded me of the stellar performance of emerging markets after the GFC:

“EM economies set to outperform

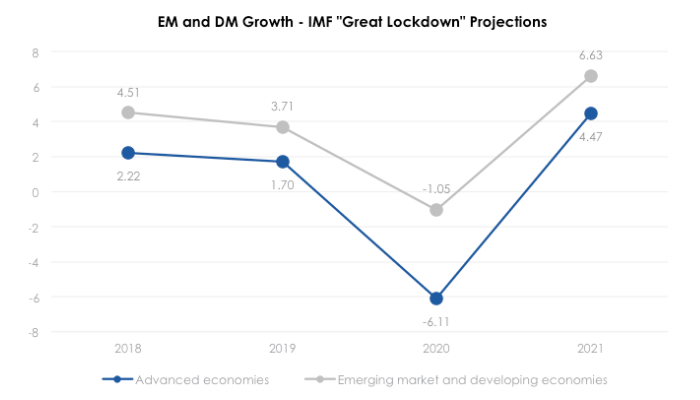

Below you see the IMF’s global growth outlook. What jumps out at us most is that EM growth suffers dramatically less, just as happened in GFC. That a 1% drop in EM growth is expected in 2020 in the backdrop of a 6% growth decline in DM, is miraculous. It is similar to what happened during the GFC, when EM growth barely registered a recession. These two events are arguably the worst global financial/economic crises in the past 100 years, and yet following the GFC, EM turns out to have thrived as the crisis abated, and it looks set to do the same again.

The reasons for EM’s growth resilience during the GFC appear intact in the current crisis – its fiscal and monetary buffers. Plus, the wave of fiscal, and risky-security-purchasing monetary policy is a huge opportunity-seeking wave, as lockdowns end. We see EMs performing as well as they did after the GFC, because their preceding conditions are similar, and because DM stimulus is unprecedented and anchors asset prices directly”.

Source: Van Eck

In times of economic crisis and global recession, emerging markets have proven to be a viable option. At the moment, their sharp V-shaped rebound shows their resilience, especially when compared to the slower, U-shaped rebound of developed economies as they continue with their cautious reopenings.

The content of this post is general in nature. Any general advice has been prepared by Allworths Wealth Management Pty Limited AFSL 457 155 without reference to your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider the advice in light of these matters and, if applicable, the relevant product disclosure statement before making any decision.